Dracula

Table of Contents

Here are some notes on Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (1897), various films and other spin-offs based on it, the historical Dracula (Vlad III), and vampire lore in general, as well as a running commentary on the timeline of the book. The page is still under construction and liable to change.

Warning: This page will contain blood-curdling horrors, very silly jokes, and SPOILERS galore. Therefore:

Enter freely and of your own will

– Dracula

The impetus for this notes page came from the DraculaDaily project, which I’ve followed since 2023. Dracula is an epistolary novel, told in diary entries, letters, and newspaper clippings; everything that happens has a date. The good people behind DraculaDaily realized it would be fun to order the entries strictly chronologically in an e-mail newsletter, so people can follow and discuss the developments in the novel day by day as they unfold from 3 May to 6 November. A big hand to them, and thanks to you guys on Mastodon for the company along the way. My #DraculaDaily musings on Mastodon make up nearly all the annotated timeline, and kind of assume that you’re reading along.

This is a very large page (~8.5 MB with images). So during DraculaDaily season, you will find a copy of only the current date’s entry at https://christianmoe.com/en/notes/dracula-daily.html.

Background reading

My background reading has been entirely unsystematic, but two books in particular proved invaluable companions during DraculaDaily, and I think anyone with a serious interest will require them:

- My battered old copy of Christopher Frayling’s Vampyres (1991), whose overview essay “Lord Byron to Count Dracula” includes the marvelous 21-page table “A Vampire Mosaic,” covering vampires in folklore (including celebrated “real” cases that were subject to official investigation), prose, and poetry 1867–1913. It also includes a selection of literary forebears (the only notable omission is Carmilla); Stoker’s short story “Dracula’s Guest”; some essays putting the Count on the psychoanalyst’s couch; and a discussion of Bram Stoker’s working notes and research readings.

- Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula have since become far more accessible in facsimile edition with annotated transcription thanks to the editorial pains of Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller (Stoker 2008).

I have not had access to Leslie Klinger’s annotated edition of Dracula (though I’m the happy owner of his annotated Lovecraft collection).

I have found food for thought in some contributions to relevant volumes in the Palgrave Gothic series (Crişan 2017; Wynne 2016) and the international scholarly Journal of Dracula Studies, which I am toe-curlingly happy to report is an actual thing that exists (or at least was published regularly until 2018 and remains accessible online).

The Count and I

My formative experiences with Dracula started with Norwegian public broadcasting (NRK). I first learned about vampires from the children’s comedy TV series Brødrene Dal og professor Drøvel. I was seven and scared, though possibly not as scared as Dracula, considering where he’s headed. The same crazy bunch later made a full-length vampire-comedy movie, the title (“Something completely different”) perhaps betraying their aspiration to be Norway’s answer to Monty Python. I first met Stoker’s novel as a radio drama (NRK radio, 10 July 1983). We were on holiday, I was nearly twelve, and I had a wonderful time listening in bed in some dark corner of an unfamiliar house. At around the same time, some of Marvel’s Tomb of Dracula comics were published in Norwegian, and I read whatever I could get my hands on. It would be another year or two until I actually read Stoker’s novel, in English.

The Dracula movie, as far as I’m concerned, is Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), and probably always will be; Winona Ryder will certainly always be the Mina.

(I had seen a few others, but none of the classics: Herzog’s 1979 Nosferatu remake left me cold. The Filipino 1982 production Darakula went a bit over my head on account of my failure to learn Tagalog. Polanski’s 1967 The Fearless Vampire Killers was forgettable fun, but I enjoyed the sets and costumes.)

As to secondary literature on the “real” Dracula, I checked out a couple of books in the library, including something by Gabriel Ronay, probably The Myth of Dracula (1972). At an impressionable age, I was thus introduced to the Impaler’s impaling and Elizabeth Bathory’s skincare routines in loving and colorful detail. (For what I’ve read since, see Background reading; References.)

I re-read Dracula as a grown-up (it came pre-loaded on my early Kindle), and wondered – as I so often do – how I’d got through the prose the first time, especially all Van Helsing’s cloying tributes to Mina. Oddly, I found it much more enjoyable this time round. Best enjoyed in small portions, perhaps.

Annotated timeline

TODO Summary

Daily

This is a running commentary on the book’s events in chronological rather than narrative order. It ranges from flippant comments and pastiches to sort-of-scholarly background and attempts at analysis and alternate readings.

3 May: Mr Harker is rolling

Figure 1: Keanu Reeves as Jonathan Harker in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Jonathan Harker, a young solicitor from England, is traveling to Transylvania, diligently writing up his diary in shorthand as he goes. We catch up with him as he reaches Bistritz (Romanian: Bistrița, fig. 2) on 3 May 2023, having travelled via Munich, Vienna and Budapest.

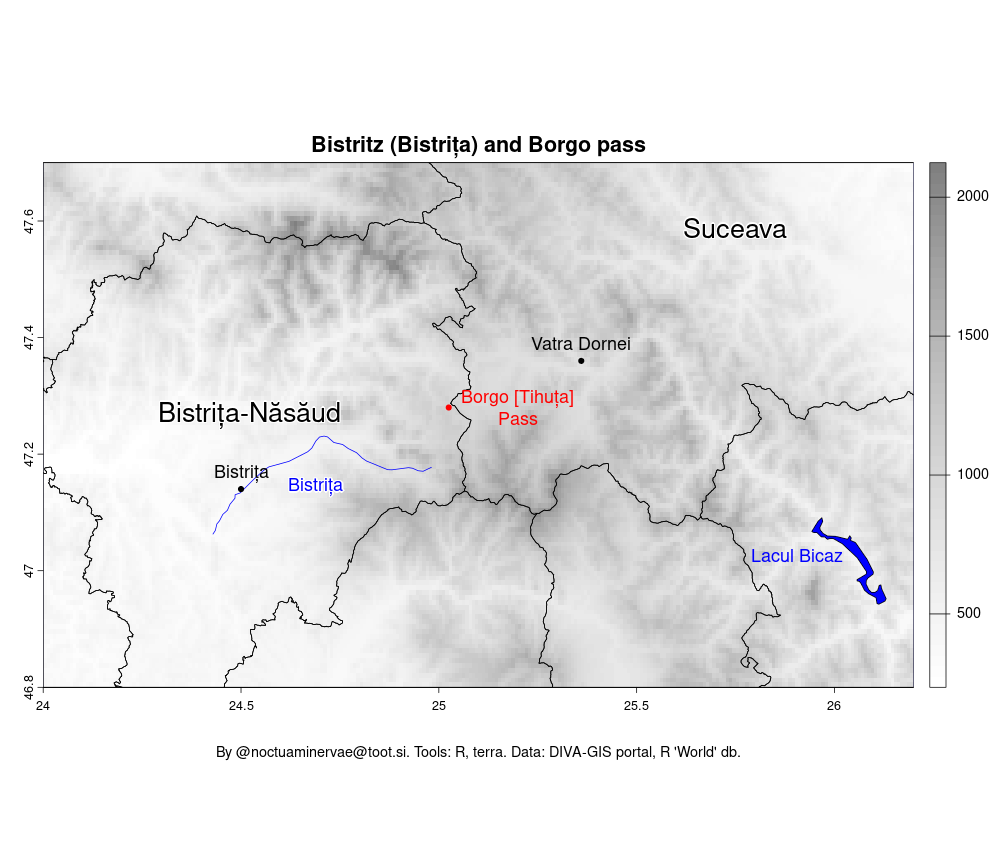

Figure 2: Bistrița on the map of Romania

Here’s a close-up of where Jonathan is at, and where he’s heading. The town is local river (from a Slavic root meaning “clear”). You’ll find the “Borgo” pass, where Dracula’s carriage awaits, on maps as Tihuța. Also labeled is Suceava County, which now contains part of Bukovina, the historical region towards which we’re going (the other part is in Ukraine).

Figure 3: Bistrița, the Borgo pass, and part of Bukovina

Jonathan has done some research on Transylvania, and informs us:

In the population of Transylvania there are four distinct nationalities: Saxons in the South, and mixed with them the Wallachs, who are the descendants of the Dacians; Magyars in the West, and Szekelys in the East and North. I am going among the latter, who claim to be descended from Attila and the Huns.

(Jonathan Harker’s diary, 3 May)

For those confused by Jonathan’s ethnic breakdown: Very roughly, and in today’s terms, the Wallachians would be Romanian-speakers, the Magyars and Szekelys would be Hungarian-speakers, and the Saxons German-speakers. Wallachian (a political/regional term) reflects the old word Vlach for Romance-speaking peoples in the Balkans generally, and thus also serves as an old name for the Romanians.

4 May: The eve of St George’s Day?!

Today’s date presents us with a very minor mystery. Jonathan’s landlady is warning him not to brave the powers of darkness on this of all nights, the eve of St George’s Day. But as an Englishman might be expected to know, even as Protestant an Englishman as Jonathan (who thinks the crucifix a bit idolatrous), St George’s Day is April 23, not May 5! Jonathan, however, is unfazed, because he has done his homework, and he knows … what? See: Sacred time in Transylvania.

5 May: Ordog, pokol, stregoica

Thought experiment. Might a (non-vampirical) Transylvanian nobleman, fallen on hard times, concoct a get-rich-quick scam involving leases to land with alleged buried treasure? And what better way to spread the word to moneyed City types than letting a London solicitor see glimpses of alleged treasure-hunting activity on a memorable nighttime ride? (toot)

Today’s entries are full of great quotes:

“Enter freely and of your own will.”

Yeah, thanks but no thanks, you very normal person.

(Some of us have been wondering if this tricks the visitor into some kind of magical forfeit. The editors of Stoker’s notes say this invitation is not found there, which suggests it’s not a piece of regional folklore that Stoker happened on in his research, so we’re free to interpret it as we like.)

“Listen to them – the children of the night. What music they make!” 🐺🎶🐺

Sometimes you can’t be sure if it’s Dracula or Lloyd Webber’s Phantom in that opera cape. Btw, speaking of Children of the Night, Dan Simmons’ modern Dracula novel by that title (1992) is a good, tense, atmospheric read if you like your vampires naturalistic and blended with real-world horrors like Ceaușescu‘s secret police and AIDS orphanages.

“Ah, sir, you dwellers in the city cannot enter into the feelings of the hunter.”

A common stereotype about latte-sipping urbanites among rural folk everywhere. Will ultimately prove ironic.

A note on the words Harker overhears:

- Ordog

- Satan [more properly ördög, a Hungarian word for devil, of unknown etymology].

- Pokol

- hell [also Hungarian, from a Slavic root]. The Hungarian terms can be traced through Stoker’s notes to Magyarland (London: Sampson Low, 1881), a book by an anonymous Fellow of the Carpathian Society, identified as Nina Elizabeth Mazuchelli (Stoker 2008, 201–3).

- Stregoica

- witch [presumably Romanian strigoaică]. The source for this, as for much of Stoker’s knowledge of Dracula’s home region, is An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (Wilkinson 1820), (London: Longmans, 1820), where it’s identified with the Italian strega. I think Romanian has independently inherited the word and its connotations from Latin, though (strix, owl; striga, night-hag in bird form). Romanian strigoi (pl.), including the strigoaică (fem.sg.), are basically vampires.

- Vrolok, vlkoslak

- werewolf/vampire [corruption of a Slavic expression, see below]. The source for vrolok/vlkoslak is Sabine Baring-Gould’s compendious Book of Were-Wolves (1865), but the words have been through a wringer. Vrolok is Stoker’s (further) corruption of vrkolak, said to be used by Slovaks and Bulgarians and connected with the Greek (βρυκόλακας, vrykolakas); vlkoslak is a misspelling of the Czech vlkodlak (Stoker says Serbian, but that would be vukodlak). All of these stem from a Slavic compound meaning (a man in) “wolf-skin”.

While we’re at it, @authorlevai has informed me that “God’s seat!” should be “Isten széke” in Hungarian, not “Isten szek.” Still, Jonathan clearly has an amazing ear for languages, and I really covet that polyglot dictionary of his.

(thread)

7 May: Dracula – American girl-boss abroad

Carfax is very much a fixer-upper, but that’s probably just the ticket for the Count. He’s like all those American ladies who leave the rat race and their exes to renovate a dilapidated estate in Provence or Tuscany in blessed solitude, and then reluctantly get drawn into the charming and colorful life of the locals and into the romantic relationship they have sworn never to risk again. This is shaping up to be a cozy read!

8 May: Dracula – model immigrant, Balkan strongman

Dracula has done his homework. He has studied English society, he has well-considered and realistic expectations as to the welcome a foreigner can expect, and he is keen to master the language. Clearly he also has ample means of support. In short, Dracula is a model immigrant, eager to become integrated. I’m starting to wonder where the conflict is even going to come from in this story.

At the same time, he’s extremely on brand as a Balkan strongman:

- Rants about his proud history fighting the “Turk”, skipping the bits that fit awkwardly in the narrative (his Ottoman-vassal dad leaving him an Ottoman hostage; he himself invading Wallachia with the aid of an Ottoman army, and fleeing back to the Ottomans; massacring civilians, including busloads of Christians)

- Plugs an utterly bonkers national origin myth (the Ugric peoples descending from the Iceland Norse?!)

- Ought to reflect more (Balkan strongmen don’t reflect much on their wrongheaded views; Dracula has no reflection in any surface).

To be sure, there is nothing uniquely Balkan about his behavior, though the Balkans have certainly been cursed with their share of such “leaders”: it’s on brand for fascists everywhere, mutatis mutandis. And yes, I do think a Dracula who is a 500-year-old nobleman, set in his marauding ways, would definitely belong to the extreme right, no matter that he can also be interpreted as a metaphor for the creeping menace of communism.

Maybe it won’t be such a cozy read after all.

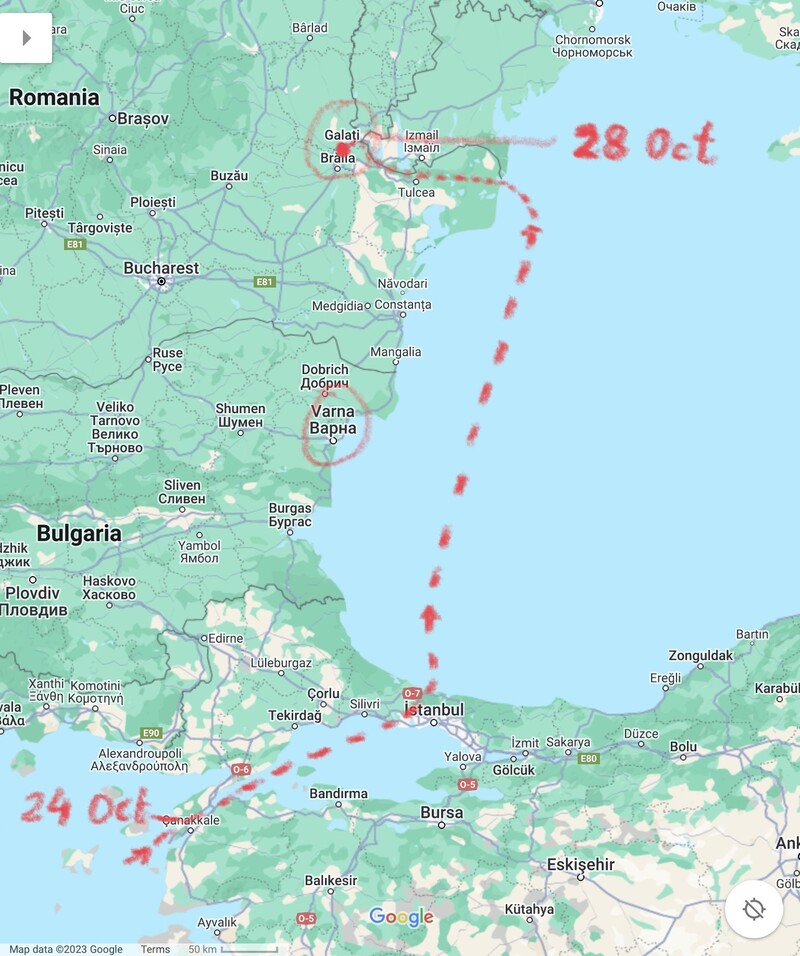

PS. Here I assumed that the Count is identical with that first Dracula he mentions, who must be Vlad III Ţepeş (“the Impaler”) aka Vlad Dracula (d. 1476/77), son of Vlad II Dracul. I’ll generally go on assuming that; it is the customary assumption, and a later discussion in the novel seems to confirm it. However, in another discussion later in the story (28 October), our heroes seize on the Count’s words about “that other of his race” who fought the Turks at a later date, and seem to identify that person with the Count. Hans Corneel de Roos, who has pointed this out, identifies the “other” as Michael the Brave (Mihai Viteazul, r. 1593–1601), who indeed retreated across the Danube but returned to attack the Turks again. Ultimately, he thinks Stoker used this ambiguity to “provide a convincing backdrop” while avoiding too precise details (de Roos 2017).

9 May: Miss Mina Murray has entered the chat 😍

It’s nice to see a woman and her fiancé share a passion for stenography, which is starting to sound like a major plot point. I think they’re going to be very happy. (toot)

Figure 4: Winona Ryder as Mina Murray at her typewriter in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

11 May: A letter from Lucy

Lucy fancies that it is hard to read her thoughts, and there is a certain sense in which uncharitable readers might agree. (toot) (Also see: Mina vs Lucy).

12 May. Cape billowing out like great black wings

We who are steeped in Dracula lore see this scene very differently from Jonathan:

- Jonathan

- Cape billowing out like great black wings, he climbed head first down the wall like a —

- Reader

- (mouths) Bat.

- Jonathan

- — lizard.

- Reader

- A lizard?! A lizard with wings?

- Jonathan

- (whips out a dog-eared copy of Fauna of Southeast Asia) Yes, one of the several flying lizard species of the genus … (pauses theatrically) … Draco.

15 May: Castle Dracula, the ladies’ parlor

Jonathan is a captive in this scary castle, and the supernaturally terrifying owner has warned him not to fall asleep in any rooms not his own. So now he’s gone exploring a panoramic room clearly “occupied by the ladies in bygone days,” writing his diary by moonlight, and feeling “a soft quietude” come over him. You see where this is going. Things are about to get scarily sexy or sexily scary.

Meanwhile, I had some questions about femininity and modernity (thread): Jonathan is finding some comfort in the room. Why? Well, the Count’s not there. But beyond that, two things suggest themselves.

It’s a ladies’ room, a feminine sanctuary. You can see the attraction to Jonathan after weeks on his best subservient behavior with a hyperdominant male (albeit one who makes his food and bed). The irony in Jonathan’s seeking security in the feminine is about to bare its fangs, though. And I think this is a piece of a larger theme.

So I wonder how much of Jonathan’s behavior, besides repairing to the ladies’ chamber, can be coded feminine/effeminate? Possibly nothing, in the 1890s context. In the 1890s the shift to what will become the female steno pool has begun, but men of affairs still practice their shorthand themselves, or have male secretaries. And journalling is even less of a gendered genre than later “Dear Diary” stereotypes would have it.

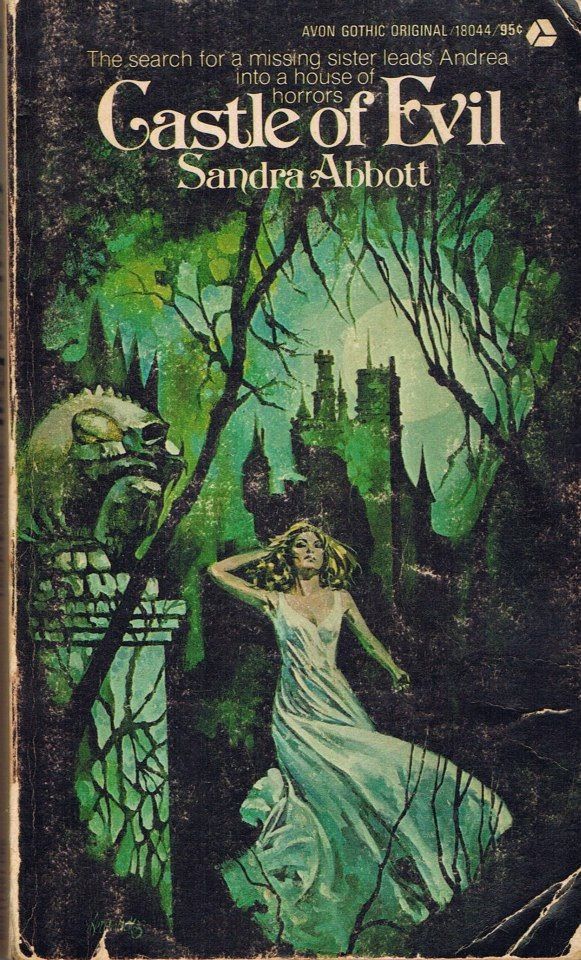

Figure 5: Example of the neo-Gothic novel

But consider the bigger picture: A newcomer to a gloomy old castle replete with dark secrets from which he must seek to escape, Jonathan faces the predicament of the Gothic-novel heroine, though it is perhaps clearer in our day after the wave of neo-Gothic paperback novels (fig. 5) than it was at the time of publication.

There’s a sense of modernity here, and its rationality is reassuring, although “the old centuries” have irrational powers which “‘mere modernity’ cannot kill.” Another theme that will recur.

But what exactly is it that is “nineteenth century up-to-date with a vengeance” in this scene?! The room is ancient, the moon outshines the lamp, the table is oak, and while Jonathan may feel a shorthand diary is very 1890s, it’s hardly new tech.

I’m guessing part of the modernity lies in the large windows, unusual for an old castle. And also in the shorthand: Though stenographic systems go back centuries, fascination with shorthand peaked in the Victorian age (“Like Esperanto a generation later, shorthand spread through a counter-culture of early adopters” – Leah Price) and waned by the start of the 20th century when it become women’s work.

But 19th-century Western social history really isn’t my field; I may be wrong.

16 May: An agony of delightful antici---

Figure 6: Vampire sister (Monica Bellucci) thinks Harker (Keanu Reeves) is a total snack. (Detail from Bram Stoker’s Dracula.)

—pation.

Jonathan, a virtuous young Victorian solicitor, finds himself about to get his jugular cherry popped in a foursome with three steamy vampire “sisters.” There is wicked, burning desire, languorous ecstasy, licking of voluptuous lips. And for all his mortal fear and his brief pang of shame at the thought that his fiancée might find out, he’s here for it.

(As was I at his age, when this film came out. Hell, I’d have let Monica Bellucci rip my throat out any time she liked.)

There’s some intriguing characterization here: Dracula, looking at Harker’s face, whispers that he (Dracula), too, is able to love. Still, I think Frayling nails it when he calls the vampire relationship “haemosexual” rather than homosexual (Frayling 1991, 385–89).

The vamps have entered popular culture as the “brides” of Dracula, but their actual relationship to Dracula and each other is not clear, apart from the fact that they call each other “sister” and that Dracula provides for them. “Sister” may be a honorific, so it doesn’t tell us much.

And where does Jonathan know the blonde from? Possibly from the tomb of Countess Dolingen of Graz (d. 1801) in “Dracula’s Guest” (1914), a separate Stoker short story linked to his early ideas for the start of the novel, where Jonathan would have some harrowing experiences already in Munich. But this encounter cannot have taken place in the novel’s universe, or Harker would not be in such good shape when we find him traveling on.

19 May: Dating letters

Dracula wants Harker to write some letters home with future dates, indicating to Harker the span of his own life.

Pedantic nitpicking: Harker got from Bistritz to Dracula’s castle in a single memorable night between 4 and 5 May. Why would he need nine days for the return trip, as suggested by the dates Dracula demands on the letters?

Of course, Dracula wants to keep Harker’s associates in the dark and reassured for as long as possible. But above all, he must make it look like Harker has left the castle alive. So why risk an implausible time gap in Harker’s testimony?

I mean, Dracula knows all about England. He must know that this won’t be overlooked if Harker’s boss, or his fiancée, engages the services of a certain consulting detective in London who doesn’t even overlook a dog not barking.

24 May: A proposal; Victorian medical equipment

Lucy may be a bit bubbly, but here she shows good sense. Toying with a lancet while proposing marriage? That’s kind of a red flag, Dr Seward.

It’s also kind of an ironical foreshadowing. Lucy turning down a suitor with an unnerving penchant for bloodletting? Out of the frying-pan, etc.

Figure 7: Tortoise-shell bleeding lancet, ca. 1890, via Health Museum of South Australia

25 May: Hell has its price

Dr Seward, Lucy’s intellectual suitor, despondently throws himself into work on the patient Renfield, on whom more anon. He asks himself under what circumstances he would not avoid hell, quotes Sallust on corruption (omnia Romae venalia sunt, in Rome all are for sale) and hints that “Hell has its price” – before interrupting himself with a Latin “enough said” (verbum sapienti sat est, a word is enough to the wise). As if toying with the idea of some unspeakable deed. The unethical research method he was chiding himself for? Or something else?

Quincy Morris, the irrepressible Texan, suggests a boys’ night out. It turns out all three suitors are old buddies. Quincy and Arthur in particular are manly men who have bonded on hazardous globetrotting wilderness adventures.

Remember Dracula’s dismissive “you dwellers in the city cannot enter into the feelings of the hunter” to Harker (5 May)? He may have underestimated the opposition. The hunter still awakens in the urbane Victorian-era Anglo-Saxon sportsman.

(Yes, I seem to be getting into an argument about the manly virtues that our friends must find to repel the foreign threat to their women and their precious bodily fluids. We’ll see how it goes.)

26 May: Three men walk into a bar

We now have an idea of most of the characters, but Lucy has been so coy about her new fiancé, Arthur Holmwood, the future Lord Godalming, that – if not for Quincey’s reminiscenses – one might almost fancy Arthur the vampire of the story, a Lord Ruthven under a new alias.

Fortunately, now that Quincey has written to him, Arthur will have to respond. Here one might expect a great outpouring of Arthur’s heart, brimming with characterization. Right? Wrong. As a character in an epistolary novel, Arthur really has one job, and he’s shirking it.

Anyway: three men walk into a bar.

A Texan with a Bowie knife, a doctor who fidgets with surgical tools when agitated, and the upper-class git who just snatched their dream girl.

Here one might expect a literal outpouring of the heart.

28 May: Enter the “Szgany”

One really gets the feeling that Dracula is enjoying his cat-and-mouse games with Harker. Entering into the spirit of the hunter, so to speak.

Meanwhile, we are introduced to Dracula’s “Szgany” minions. Of all the Carpatian “whirlpool” of foreign races, the Roma arguably get the worst explicit press in the book.

31 May: Into the silence

Spare a thought for Harker’s fraying nerves now and then over the coming 16 days of terrifying quiet. He’s far from home, alone, pretending to be a guest, knowing himself the prisoner and prey of monsters, knowing he’ll soon be killed, rightly fearing that will only be the beginning. He has only his diary to confide in.

For the next 16 days, he doesn’t.

And someone just took away his comfort blanket.

5 June: Dr Seward asserts his authority

He gives Renfield three days to get rid of his flies.

17 June: The Slovaks arrive

The slow, silent shredding of Harker’s sanity is interrupted by the arrival of some Slovaks with a delivery of empty boxes. Harker’s attempt to contact them is dashed by Dracula’s fiendishly clever and unexpected stratagem of, uh, locking his captive in.

(If Mina had been in his shoes, over the past few weeks she would have drawn up a dozen concisely phrased but carefully itemized escape plans and successfully executed the most plausible one. Just saying.)

A few glosses:

- Slovaks

- migrated in numbers to various parts of today’s Romania in the 18th and early 19th c, some seeking a freer climate to be Protestant in, others a fertile climate for farming in imperial borderlands depopulated by war.

- Leiter-wagon

- already glossed as “the ordinary peasants’ cart” by Harker on 5 May. From German Leiter, “ladder,” because the sides of the cart are shaped as ladders.

- Hetman

- here probably just headman or leader, in a loose usage which had spread beyond its original use for a Polish-Lithuanian commander or Cossack leader.

18 June: More flies

It’s been two weeks since Dr Seward gave his mental patient Renfield three days to ditch his flies, and you know what? He hasn’t. Ok, he’s feeding them to spiders now, but also he’s getting more flies.

This doesn’t reflect well on Seward’s authority. Or perhaps on his ethics? Is he trying to to keep his patient “to the point of his madness,” as he chided himself for back on 25 May? Wanting to see where it goes? If it’ll end with spiders? (Narrator: It won’t.)

24 June: More wolves

Dracula’s treatment of the woman looking for her child again confirms our picture of him: aristocratic but not too proud to do menial work or appear common, a solicitous host, a reliable provider, good with animals, and ready to dispense swift mercy to those in anguish. No, kidding. We get our most shocking confirmation yet that he is a heartless, evil monster.

Also some new Stokerian vampire lore: Though Dracula himself has so far appeared robustly physical (a few odd tricks of optics apart), vampires can also take on more ghostly, ethereal forms, coalescing from motes of dust in the moonbeams, and they can have a hypnotic effect.

Meanwhile, as I was reading this in the real world back on 24 June 2023, the Wagner mutiny was happening in Russia, as the disaffected mercenary group ranged hundreds of kilometers inland against no real opposition. Hard not to see it as a werewolves-vs-vampires standoff: Vlad the Vampire vs. Wagner the Werewolf, if you’re familiar with Wagner, the Wehr-Wolf (1846–7) by George W. M. Reynolds, a wild ride of a Gothic novel (very unlikely to have influenced the later Nazi fascination with Wagner, werewolves, and the, uh, Wehr-macht).

25 June: Jonathan has a lie-down

Jonathan has finally found his courage and initiative, and has caught his dread enemy at his most vulnera NO JONATHAN NO WHERE ARE YOU GOING GET A STAKE NO DONT LIE DOWN TO THINK JONATHAN STAKE GET A STAKE DRIVE IT THROUGH HIS HEART YOU BLITHERING

Get this: Jonathan has learned that Dracula is helplessly inert in the daytime. He has found him in his lair and could have rid the world of the fiend forever. But he thought Dracula looked at him funny, and decided to have a lie down and a think instead. Four days of inaction pass until the next note.

Oh well, as someone who turned tail and fled the Norwegian National Library on his first visit because I thought the architecture of the entrance hall was looking at me judgmentally, I guess I can’t blame him. Spoiler: A bunch of people are entitled to blame him, though, including some lovely young ladies, a shipload of sailors, and several Hampstead families.

29 June: What music they make

Now the children of the night are making music again. I love the image of Dracula controlling an orchestra of wolves like a conductor with his baton. When the inevitable happens and Dracula gets Disneyfied, this could be a great song number.

30 June: All or nothing

After a really half-assed attempt to kill Dracula – a glancing blow on the forehead with a spade is NOT HOW YOU KILL A VAMPIRE, Jonathan – and much procrastination, Jonathan is now trying to gain his freedom from the vampirettes by either succeeding in climbing the castle walls, or failing.

And what’s with the 50 boxes of Transylvanian soil Dracula is shipping? Some thoughts under Blood and soil.

1 July: Swallowed a fly

Renfield is doing his impression of “There Was An Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly.”

Dr Seward makes an unconvincing show of imposing some discipline on his patient, but really he is just raptly taking case notes with all the professional ethics of someone slowing down to gawk at a car crash, isn’t he?

6 July: The Demeter sets sail

The Demeter sets sail with an unreliable passenger manifest of zero, but loaded with a familiar cargo of boxes of earth, and, erm, victualed with a crew of nine.

Of all the imaginative subplots and iconic scenes in Stoker’s Dracula, I think none instills a growing sense of terror more effectively than the terse log entries from the voyage of the Demeter and her doomed crew. Poor souls.

Stoker took his inspiration for the ship from an event involving a Russian schooner, the Dimitry (see 8 August), but changed the name to the more classical-sounding Demeter, transforming a god-fearing Orthodox ship, presumably dedicated to St Demetrius, into the vessel of a pagan goddess.

Demeter, of course, is the Greek goddess of fertility and the harvest who grieves for her daughter Persephone (Kore). Persephone was abducted and raped by the prince of the underworld, and, having eaten some pomegrenade seeds, is doomed to spend half of all her days with him beneath the earth as queen of the dead: a rather vampire-like fate. (Though unlike a vampire, she walks the world of the living when the sun shines brightest, as Demeter’s joy at their reunion brings summer.)

8 July: Unconscious cerebrations

Dr Seward’s mad doctoring intensifies.

Note to self: hereafter make sure to call all my vague notions and dim feelings “unconscious cerebrations.”

19 July: No kittens

I’m relieved that Dr Seward draws the line at kittens. Stand firm, doctor: Renfield may find the rejection hard to swallow, but then, he’s about to find out what hard to swallow really means.

20 July: Scientific progress goes bump in the night

- Renfield independently rediscovers why people tend to pluck birds before eating them.

- A newly discovered mental disorder, Seward’s zoophagous mania, has been proposed. (Spoiler: It hasn’t made it into the DSM-5. Yes, I checked.)

- But Dr Seward dreams of greater discoveries, and though he’s

only monologueing at his diary for now, he’s really leaning into his mad doctor persona, isn’t he?

I mean, when you start talking – in the same breath – about (1) finding the keys to lunatics’ fancies, (2) vivisection, and (3) how congenitally exceptional your own brilliant brain might be, and drop dark hints that (4) you might be tempted into mad science for a cause – why, the next moment you’re Elon Musk haphazardly tormenting monkeys for data to justify human trials so you can sink your brain implants into real people brains to save mankind from woke – but I digress

22 July: Captain’s log: “All well”

Narrator: [chokes on coffee]

24 July: The Demeter is in a funk again

To lose one seaman is unfortunate; to lose two seems like carelessness.

24 July: Whitby

Mina has come to beautiful seaside Whitby, Yorkshire, to stay with her well-to-do airhead friend Lucy Westenra, soon to be Mrs Arthur Holmwood. It promises to be a fun and relaxing summer, with the atmospheric ruin of Whitney Abbey as a spooky backdrop, but with all the modern convenience of rooms at the [Royal] Crescent, built in the 1850s.

I went to Whitby at the end of July myself in 2024, nerding hard. Whitby Library saved its no doubt sorely tried librarians from me walking in and asking to see their copy of William Wilkinson’s Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (1820), in which Stoker first spotted the name “Dracula,” by the simple expedient of keeping closed all Wednesday.

Here’s a picture of spooky Whitby Abbey. Mina’s 14 August entry could serve as a caption: “The setting sun, low down in the sky, was just dropping behind Kettleness. The red light was thrown over on the East Cliff and the old abbey, and seemed to bathe everything in a beautiful rosy glow.”

Figure 8: Whitby Abbey. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

Oddly, few B&Bs by the Crescent (pictured) seem Dracula-branded, but the self-catering apartment Bram’s View at no. 6 claims to offer, well, Bram’s view from when he stayed.

Whitby does sport a Dracula Experience, a Dracula Festival, etc. etc. Whitby Abbey has recently been (groan) “revamped” by British Heritage, and in 2022 it set a record for the Largest Gathering of People Dressed as Vampires (1,369, but how do you actually tell?).

Figure 9: Royal Crescent, Whitby. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

Over the next weeks, we will be treated to many a proud demonstration of Stoker’s keen ear for dialects, God grant us fortitude and understanding. Ageeanwards the end of better understanding the old man, Mr Swales, here’s a glossary (in order of appearance in the passage:

- comers

- visitors

- creed

- to believe

- gang

- to go — walk

- ageeanwards

- towards

- crammle

- to hobble as with corns

- aboon

- above [but used for “down” in Dracula – editors’ note]

- grees

- stairs

- belly-timber

- food

These glosses are verbatim from Stoker’s notes (Stoker 2008, 142–49). Stoker, in turn, cites F. K. Robinson, A Glossary of Words Used in the Neighbourhood of Whitby (London: Trubner, 1876).

Also, Mina’s talk with the old man is quite documentary. Stoker records a conversation with three old fishermen on 30/7/90 (Stoker 2008, 150–53). He heard some yarns about lost whalers, and also asked about the local legends Mina refers to; as far as the editors can make out, he notes: “These men said if legend of bells at sea & white lady in Abbey window. Then* things is all wore out” (153).

(*) Should probably read “them things,” as in the novel).

26 July: Somnambulism

Mina is apprehensive about the odd one-line letter from Jonathan; as we know, she’s right to be. Trust your feelings, Mina.

Meanwhile, Lucy is sleepwalking. She’s done so before, and her father had the same affliction. Considering how things turn out, it seems she’s a congenital psychic sensitive, already responding to Dracula’s magnetic pull from out at sea.

Stoker’s notes (2008) include some quotes from an 1808 book about dream theory (F. C. & J. Rivington, The Theory of Dreams, 2 vols., London). He showed interest in ideas about dreams as visionary/oracular and sleep/dream as a state akin to death, and noted cases of people falling into a cataleptic state where they could easily be taken for dead. (Such disorders, of course, are among the many rationalist explanations for the belief in vampirism.) But nothing about somnambulism as such.

The female victim sleepwalking towards the vampire “under the strong influence of some eccentric dream” figures in the penny dreadful Varney the Vampire, which provided a number of vampire tropes used in Dracula (Frayling 1991, 40–41). Sir Francis Varney seems surprised at his powers, though, while one imagines Dracula using his fatal attraction deliberately.

Horror’s premier somnambulist remains Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), which also involves sleeping in a box, and an asylum.

27 July. Prayers.

“[Lucy] has lost that anæmic look which she had. I pray it will all

last.”

Oh, Mina. 😥

1 August: All them tombsteans

Figure 10: Churchyard of St Mary’s, Whitby. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

So, the British man in the street says that wafts and white ladies, boh-ghosts and bogles are just lies, or if they ever existed, now they’re “all wore out.” And indeed we meet no native apparitions. His skepticism extends to the memorials of the dead: they are not even buried in British soil. Contrast the vigor of the vampires in Transylvania, the holiness of its soil soaked with ancestral blood, and the powers of its “old centuries” against “mere modernity.”

More glosses of Whitby dialect from Stoker’s notes, in order of appearance in Mr Swales’ 1 August rant. (In a discussion, I described Mr Swales as “kind of a one-man-band Spoon River Anthology” of cynical remarks on his late townsmen.)

This list is probably missing a few words that a human (one that doesn’t bore easily) would find in Stoker’s notes. I couldn’t resist writing a little script to automate this, but linguistic computation isn’t my strong suit, so anything besides basic punctuation, plurals, and capitalization might confuse it.

- ban

- curse

- waft

- ghost

- boh-ghosts, barguests

- terrifying apparitions [more specifically: barghests, monstrous black dogs of Yorkshire folklore; possibly an inspiration for an event to come shortly.]

- bogle

- [no gloss, presumably ghost]

- anent

- concerning

- bairn

- a child

- dizzy

- half-witted

- air-bleb

- bubble

- grim

- a ghost

- illsome

- evil disposed

- scunner

- to scare

- hafflin’

- a half wit

- airt

- quarter or direction

- scowderment

- confusion

- yabblins

- possibly!

- poorish

- few, small number

- balm-bowl

- a chamberpot

- kirk-garth

- churchyard

- consate

- to imagine

- aboon

- above [but used for “down” or “below” in Dracula]

- lay-bed

- a grave

- toom

- empty

- aftest

- hindmost

- hap

- to bury

- antherums

- doubts

- gawm

- to understand

- lamiter

- a deformed person

- clegs

- horseflies

- dowp

- carrion crow

- addle

- live

- keckle

- to chuckle

- grees

- stairs

- gladsome

- joyful

- gang

- to go — walk

References as before (Stoker 2008, 142–49 citing Robinson’s glossary); comments in square brackets are mine.

3 August: Nightmares are made of this

Today’s events inspired me to this dreadful doggerel; apologies to Eurythmics:

🎶 Nightmares are made of this

Who am I to disagree

I travel the Med and the British Channel

Everybody’s looking for something

Demeter’s mate looks for a stowaway

Mina still looks for a letter

Lucy sleeps, but tries to go away

Dracula’s coming to get her 🎶

4 August: Him – It!

The captain has seen Him – It! – for the first time.

At about this point in the 2023 #DraculaDaily cycle, The Last Voyage of the Demeter was about to hit cinemas (stoked toot). Not starring Viggo Mortensen after all, unfortunately, BUT directed by André Øverdal, of Trollhunter fame.

6 August: Death in the air

There’s something in that wind and in the hoast beyont that sounds, and looks, and tastes, and smells like death. It’s in the air; I feel it comin’.

— Mr Swales in Dracula

Permalink to the 6 August entry:

https://christianmoe.com/en/notes/dracula#d08-06

More Whitby dialect glosses from Stoker’s notes, in order of appearance in Mr Swales’ speech:

- aud

- old [repeatedly]

- krok-hooal

- a grave

- caff

- to chaff

- chafts

- jaws

- dooal

- grief, to lament

- greet

- weep

- hoast

- mist

I’m loving the Norse influences (“greet” for “cry, shed tears”).

Mina’s “brool” is “a low roar: a deep murmur or humming” (Merriam-Webster). I am officially in love with this word.

And Mina’s “men like trees walking” is from Mark 8:24 (how the blind man at Bethsaida started dimly seeing people before Jesus laid his hands on him a second time and restored his sight completely). Not to put too fine a point on it: it’s foggy in Whitby.

I have no idea how well Stoker did with the dialects (I have a tin ear myself), but between his notes from a dictionary and his chats with locals during a summer holiday, I’d imagine he’d get right the words and patterns he knew, but get on thin ice as soon as he ad libbed.

We’ll hear more of her [the Russian ship] before this time tomorrow.

— Mr Swales

Indeed they will; and the day after, so will we.

8 August: Landfall

Say what you will about Dracula, the man knows how to make an entrance! Crashing ashore in a mystery ship steered by the storm and the hand of a dead man, then leaping out – presumably – as an immense dog.

And here’s a picture I took of Dracula’s landing site in rather fairer weather than he brought.

Figure 11: Dracula’s landing site between East Pier and Tate Hill Pier, Whitby. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

This Wiki picture of the narrow opening in the pincer-like jaws of the East and West piers shows what a freak event it would be for the storm to blow the Demeter into the harbor by chance.

Some notes:

- I think this is our first intimation that Dracula can not only control wolves, he can take their shape. In Hollywood’s rigid werewolf/vampire dichotomy, that would make him both, but I think Stoker’s Dracula is more non-binary about it. For some background notes, see Vamps and wolves.

- Remember Mina deciding to learn the weather-signs? Stoker was equally determined, and the Dailygraph’s depiction of the brewing storm reflects his notes from Robert H. Scott’s Fishery Barometer Manual (London, 1887): the show of “mares-tails” in the northwest, the southwesterly wind, the “gaudy or unusual hues” (Stoker 2008, 132–37).

- On 24 October 1885, the Russian schooner Dimitry (hence Stoker’s Demeter) blew into Whitby harbor in a force-8 gale, somehow avoiding the rocks, and was wrecked on the beach. The crew was saved. Stoker noted the incident and kept an extract from the log book of the coast guard station (Stoker 2008, 138–41).

- The line “As idle as a painted ship upon a painted ocean” is from Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, another tale of a cursed voyage where the crew all die, save for the one who lives to tell the tale.

10 August: “Perhaps he had seen Death with his dying eyes!”

Several detective mysteries here.

Poor Mr Swales’ death seems the least mysterious, whether he did fall and break his neck from fright when seeing Dracula, or Dracula snapped his neck.

The curious case of the dog in the day-time, though, is hard to explain. We know it’s the tombstone of a suicide; we know Mr Swales just died on this self-same seat; but is the dog just reacting to the psychic residue of these deaths and of the fleeting presence of Dracula? And what reduces it to trembling jelly on the tombstone? Is Dracula perhaps still around, right under their feet? Might he have taken temporary shelter in this tomb while waiting for his boxes to be delivered? I don’t think so – it conflicts with his character and his apparent dependence on his ancestral soil – but the dog’s behavior puzzles me. And so does Lucy’s.

The sensitive Lucy, who recoiled from a seat on a suicide’s tomb a few days ago, may be restless, but puts up no objection to sitting there now despite the fresh death of Swales at the same spot. (Mina too seems oddly unmoved.) Her helpless look at the helpless dog “in an agonised sort of way” perhaps suggest she recognizes its plight – another creature in thrall to the power of Dracula?

On a lighter note:

- “Severe tea” 😍 is, I suppose, nothing kinkier than tea with too much to eat.

- Fighting “the dusty miller,” I guess, means fighting back sleep; the miller’s flour dust, like the Sandman’s sand, gets in your eyes and makes them itch and close. Don’t know how common the expression was. But I almost feel I can trace Stoker’s train of thought from Robin Hood Bay to the dusty miller: one of the more memorable parts of Pyle’s Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883) was the tale of Midge, the miller’s son, and his tactic of throwing flour in his opponents’ faces.

- I’ve had discussions as to whether Mina is a New Woman, and since I wasn’t too sure about that, I should probably feel vindicated that she’s so concerned today to distance herself from that trend. But perhaps the lady doth protest too much. I certainly find it hard to picture that Mina would rest fulfilled as stenographic helpmeet to her husband for very long.

We’ve been hearing a lot about Mina’s and Lucy’s favorite seat, and we’ll hear more anon. There are several benches in the churchyard today, all look too new, and I don’t know if any is in the right spot. (I did not get on my knees, whip out my magnifying glass and search for a stone inscribed to George Canon as night fell.) Feel free to imagine it’s this one!

At least, I reason that the pictured bench is drawn far enough back from the cliff’s edge that they might have watched the captain’s funeral from there without craning their necks, but it might perhaps still be visible from the West Cliff.

Figure 13: Lucy’s and Mina’s seat? Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

11 August: On the bench

The clock was striking one as I was in the Crescent, and there was not a soul in sight.

– Mina’s diary

It’s an easy 20-minute walk for Lucy, and later Mina, but Lucy is sleepwalking, or something, and they’re barefoot in their nightgowns. They start from the Crescent:

Figure 14: The Royal Crescent, Whitby. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

At the edge of the West Cliff above the pier I looked across the harbour to the East Cliff, in the hope or fear […] of seeing Lucy in our favourite seat. […T]here, on our favourite seat, the silver light of the moon struck a half-reclining figure, snowy white. […I]t seemed to me as though something dark stood behind the seat where the white figure shone, and bent over it.

– Mina’s diary

Mina has excellent eyesight: Here’s the daylight view.

Figure 15: View from the West Cliff to the East Cliff. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

I did not wait to catch another glance, but flew down the steep steps to the pier and along by the fish-market to the bridge, which was the only way to reach the East Cliff. The town seemed as dead, for not a soul did I see; I rejoiced that it was so, for I wanted no witness of poor Lucy’s condition.

– Mina’s diary

Through narrow streets of cobblestones, perhaps ‘neath the halo of a street lamp, like this, but presumably gaslit, if lit at all.

Figure 16: Church Street, Whitby. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

The time and distance seemed endless, and my knees trembled and my breath came laboured as I toiled up the endless steps to the abbey.

– Mina’s diary

(Not endless. There are 199 of them. A fairly easy climb.)

Figure 17: The 199 steps. Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

When I got almost to the top I could see the seat and the white figure, for I was now close enough to distinguish it even through the spells of shadow. There was undoubtedly something, long and black, bending over the half-reclining white figure. I called in fright, “Lucy! Lucy!” and something raised a head, and from where I was I could see a white face and red, gleaming eyes. Her lips were parted, and she was breathing — not softly as usual with her, but in long, heavy gasps.

– Mina’s diary

You’ll have to use your imagination a bit for this one.

Figure 18: Bench in St Mary’s Churchyard. Maybe the bench? Photo: © Christian Moe 2024.

Or we can cut to Coppola’s movie adaptation, which made a whole steamy sex scene out of it, with hip thrusts suggestive of vaginal penetration in addition to the jugular kind. While the movie’s Lucy appears to be into it, we should not assume she’s in any state of consciousness to give meaningful consent to the serial predator she’s with. It’s rape. Yes, vampire stories and vampire movies are guilty pleasures.

Figure 19: The Lucy/werewolf scene from Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. © 1992 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. Detail of still used as visual quotation under provisions for fair use.

Poor Mina. What a brave and devoted friend she is! But she hasn’t seen the movie, and doesn’t know what the pinpricks of blood on Lucy’s throat mean. Let’s not tell her.

Instead, here’s some suitably innocent, sweet music to soothe her nerves as she sneaks Lucy back on muddy feet:

🎶 As we walk through the streets there’s noone nowhere

And our nightgowns are trailing and our feet are bare 🎶

— Katie Melua singing “Moonshine” by Fran Healy https://youtu.be/oZCGeu6STwg

Moonshine lyrics © BMG Rights Management. Excerpt quoted under provisions for fair use.

12 August: Jonathan turns up

Lucy’s attitude to bedroom doors reminds me of my cat’s.

But Jonathan has turned up, and the good news are en route to Mina with a stern warning not to mention anything “of wolves and poison and blood; of ghosts and demons,” so clearly they’re being set up to withhold crucial information from each other until tragedy has well and truly struck. Not my favorite plot device.

Klausenburg = Cluj (Hun. Kolozsvár), capital of the former Principality of Transylvania.

Oh, and I love this bit: “Seeing from his violent demeanour that he was English, they gave him a ticket for the furthest station on the way thither” 🤣

13 August: Bats

Today is the first mention of a bat in Dracula. After 3 months, 10 days. (Yes, we’ve seen how Dracula climbed down his castle wall in a very bat-like way, but as you will recall, Jonathan saw it differently.)

While South American “vampire bats” had been so called since the 1700s, it was only Stoker’s Dracula that established the pop-culture vampire as shifting between human form and bat.

Though antecedents can be found – here’s a great read:

Andy Boylan, “Stoker and the Bat”, Vamped.org, April 5, 2014.

14 August: His red eyes again

🧛🏻♂️ “His red eyes again.” Just a trick of the light? Or is Dracula up and about early?

I commented on Mina’s good eyesight on 11 August when, from the West Cliff, she saw in the moonlight a reclining white figure on the seat on the East Cliff. But making out glowing red eyes at that distance, as both Lucy and Mina seem to do? Must be a trick of the light, as she says. Or a psychic phenomenon, perhaps.

🧛🏻♂️ Re: movie vampire eyes, I’m partial to the slit-pupil versions: They’re predators, after all.

🧛🏻♂️ What’s that up there with Lucy on the windowsill? Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, Mina, it’s a bat.

(Probably. Can’t rule out Dracula taking owl shape, but he’s pretty consistent about being a bat here, and Lucy’s wounds are hardly from a beak.)

15 August: Lucy was languid

🧛🏻♂️ “Lucy was languid”: and if you like the word “languid” – not to mention beautiful young women spending a summer of mutual attraction and mysterious bite marks together – you should read Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) now if you haven’t already. Another great Irish vampire story and, I think, an important influence on Stoker.

(If you want a paper copy, do look for the 2019 Lanternfish Press edition for the added value of Carmen Maria Machado’s introduction and the learned references therein. It will astound you. No, I’m not going to tell you why.)

(Unexpected bonus: apparently, reading Carmilla can also harm the national interests of Belarus, where it is officially blacklisted by the Ministry of Information. 🤡)

🧛🏻♂️ Obviously Mrs Westenra’s heart condition is another device that keeps other characters from sharing crucial information, and Lord Godalming’s sickness keeps Arthur from noticing Lucy’s plight and coming to her aid.

But I wonder if there is any further significance to the theme of dying parents handing over to a new generation.

17 August: Keynes

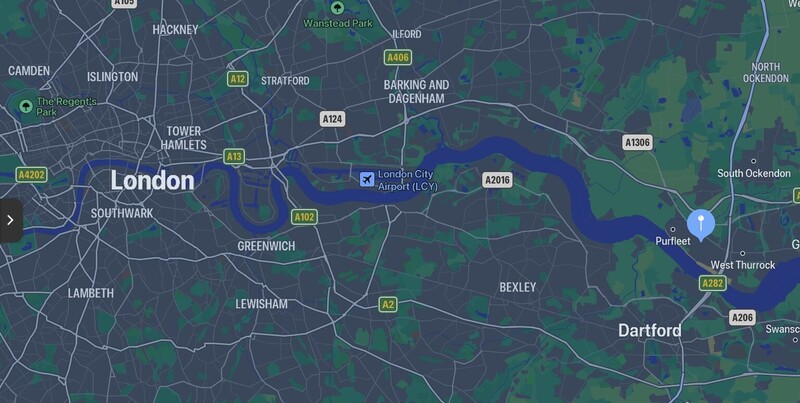

As the 50 boxes of Transylvanian soil near their destination at Carfax near Purfleet, perhaps it’s time to appreciate Dracula as a novel of fin-de-siecle globalization.

Dracula’s UK venture is sped by wagon, ship and rail, facilitated by a network of solicitors and shipping agents communicating by reliable international mail. Global trade is a mighty circulatory system, and Dracula, Bradshaw’s Railway Guide in hand, has his fangs on its pulse.

Figure 20: Purfleet on the map. Image: Apple Maps.

Though globalization thus does bring vampirical infestation with it, it’s hard to detect anti-globalist notes (or the anti-Semitic undertones they have in some quarters: the agents have names like Hawkins and Billington, not Rothschild).*

*) Not Rothschild: but a sheep-nosed “Hebrew” shipping agent named Hildesheim will eventually turn up, as if Stoker suddenly realized he’d forgotten to include a stereotyped Jew.

The novel rather celebrates a dawning age when, as J. M. Keynes wrote,

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep.

— John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (London: Macmillan, 1919)

Indeed, Keynes might almost** have been writing of Dracula:

**) But our learned and industrious Count certainly does not proceed to foreign quarters “without knowledge of their religion, language, or customs.”

He could secure forthwith, if he wished it, cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or other formality, could despatch his servant to the neighbouring office of a bank (…), and could then proceed abroad to foreign quarters, (…), bearing coined wealth upon his person, and would consider himself greatly aggrieved and much surprised at the least interference.

– Ibid.

18 August: And I dreamed I was flying

After all that’s happened, Mina and Lucy are STILL sitting on that seat.

Dracula is at his new home near Purfleet, and probably busy – Carfax sounded like a fixer-upper – so back in Whitby, the spell is lifted and Lucy’s doing better. For now. The “dream” she recalls is an out-of-body experience – suggesting she was near death, or in a state of sleep paralysis, or “traveling clairvoyance,” or seeing through his bat eyes?

Lucy’s dream of flying above the lighthouse somehow reminded me of Paul Simon’s hauntingly beautiful “American Tune,” so I started adapting it as a Dracula musical. 1st verse sung by Jonathan (“certainly misused … so far away from home”), 2nd by Mina (“I don’t know a soul that’s not been battered, I don’t have a friend who feels at ease”), bridge by Lucy (“And I dreamed I was dying”), and 3rd verse, slightly adapted, by Dracula (“I come on a ship they call the Demeter … and sing a Transylvanian tune”). However, better judgment kicked in, and I’ll spare you the full horror of my travesty.

But as noted elsewhere, there are so many Dracula musical numbers I’d love to see, and the actual Dracula: the Musical doesn’t sound silly enough.

19 August: The bride-maidens rejoice

While Lucy is temporarily free of Dracula’s sway, Renfield is filled with zeal by Dracula’s presence at Carfax, the neighboring estate to Dr Seward’s asylum. The bond between them is not clear; perhaps Renfield is a psychic sensitive, as Lucy seems to be. Renfield’s mania centers on prolonging his life by eating others, so it’s not odd that he wants to attach himself to Dracula, an expert in that field.

But it’s noteworthy that he “worships” Dracula, calls him “Master,” and apparently sees himself as a kind of disciple. And then there’s his curt dismissal of Dr Seward with a parable: “The bride-maidens rejoice the eyes that wait the coming of the bride; but when the bride draweth nigh, then the maidens shine not to the eyes that are filled.”

Incidentally, the line about the bride-maidens rejoicing is nicely developed in the movie The Invitation (2022).

Renfield is saying that people like to look at the pretty bridesmaids until the bride herself appears, but then they have eyes only for the bride. On one level, this means he can no longer pay attention to his doctor (a mere bride-maiden) now that his Master (the bride) is at hand. What it might mean on a further level, depends on what Biblical allusion we pursue.

This is not a direct quote from the Bible; rather, it’s a kind of pastiche of Biblical wedding symbolism. Several references are suggested (Psalm 45:13–14; Matt 25:1–13, which we may already have seen Quincey mangle when proposing; John 3:29; various passages on the Bride of the Lamb in Rev 19 and 21).

John 3:29 is perhaps the most promising as a key to Renfield’s thinking. In context, John the Baptist speaks of Jesus as the bridegroom and himself as a mere friend of the groom. As John humbly explains to his followers, the bride (the Church) belongs to the groom (Jesus), not to John.

Along these lines, Renfield perhaps sees himself playing John the Baptist to Dracula’s (anti-)Christ; his role is to prepare the way for the Master. If so, this will not be the last scene suggesting Dracula as a grotesquely inverted Christ figure, but more on that later.

Another notable inversion here, though, is that of gender. In John 3:29 as in other wedding passages, the Jesus symbol and focus of the wedding is the groom: “The friend who attends the bridegroom waits and listens for him, and is full of joy when he hears the bridegroom’s voice.”

Renfield switches groom to bride, and clearly the bride here signifies Dracula. Though Dracula has been clearly gendered male, and pretty toxic male at that. Perhaps Renfield’s parable is just a nod to modern wedding customs where the bride always shines the brightest; I certainly think that makes his point easier to understand for the reader. Or perhaps – just perhaps – Renfield’s queering Dracula a bit?

(Or maybe I’m just making up for my failure to get into the weeds of Dracula’s possible homosexual attraction to Jonathan. I think those weeds have been well trodden by others, though.)

20 August: Seward still bad at dating

Dr Seward’s diary today is disconcerting. He appears to think a week has gone by since the events of yesterday, and then another three days before he’s done recording for today.

Maybe someone just dated the recording wrong (Seward, Stoker, or, as we shall see, perhaps Mina). That seems to be the issue with the extra three days, at least - the date “23 August” should have come before the addition to today’s entry.

Or maybe we have an unreliable narrator.

As we’ve seen, Lucy’s “no” pushed Seward into depression tinged with decadence (as well it might – in Stoker’s original notes, he was to have been her fiancé). Maybe he’s been dipping too much into the chloral hydrate after all.

He’s also given off a mad-doctor vibe with his musings about unethical experiments on patients – and he’s set to launch another one tonight (or in three nights).

Or maybe (it struck me in one thread), I keep making him out to be less stable or having bigger issues than he is. Maybe because he’s the only character with any interesting inner life so far. But then, he is not in the sanest of environments. (His satisfaction with a “soft cringiness” in his patient would be pretty creepy – if the alternative were not a murderous violence …)

Also, he seems to be going through a bit of what psychotherapists call counter-transference – projecting his own issues onto his patients.

Yesterday and today, he’s been obsessing over his rank in Renfield’s estimation. When Renfield made no distinction between his doctor and his attendant, Seward, with his own riff on a Biblical parable, put the difference as that between an eagle and a sparrow. Ego much?

Today Seward’s feelings are soothed when he thinks Renfield distinguishes him from the others (but ironically, I don’t think it’s him Renfield is talking to).

Anyway, Dr Seward doesn’t seem entirely stable. In Sister Agatha’s judgment, Harker is about as stable as a pyramid of cards stood on its tip. And what are we to make of the captain’s wild ravings in the bottle? We have a bunch of potentially unreliable narrators here.

Or unreliable editors. Which opens up possibilities even darker than a naïve reading of Dracula. So I’ll return to them. 😬

21 August: Receipts

In which the author of The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1879) brings the receipts, so to speak.

Such subjects as the advisability of uniform filing of papers or folding of returns, of using dots instead of 0’s in money columns, or of forwarding returns at the earliest instead of the latest date allowable, may seem too trivial to treat of; yet every Clerk would do well to remember […]

– from Stoker’s “Introduction” to The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1879) 🙂

23 August: Flapping

“… a big bat, which was flapping its silent and ghostly way to the west.”

West along the winding Thames from Purfleet lies teeming London, population: about 6 million pulsing jugular veins, with no natural immunity to Carpathian vampirism, ripe for an epidemic.

But perhaps the strain is not so virulent? After all, patient zero has already quite recovered, sleeping soundly through the night with roses back in her cheeks.

Oh, and she is back in … London.

24 August: Mina + Jonathan

A lot going on here.

🧛 Mina and Jonathan tied the knot! 🥂 Good for him, I guess.

🧛 “The idea of my being jealous about Jonathan!” Indeed, Mina, indeed.

🧛 Yesterday Dr Seward recorded a bat streaking west toward London. Today Lucy records feeling ill again, like she was in Whitby, but this time at the Westenra family home, Hillingham, which will turn out to probably lie somewhere in London’s Hampstead area. Post hoc, ergo propter hoc?

🧛 “Wilhelmina”: Jonathan hasn’t called Mina this since they got engaged. Good thinking, Jonathan, keep it up.

🧛 “…unless, indeed, some solemn duty should come upon me…”: Not so good thinking, Jonathan. We realize that you are dissociating after a severe mental trauma, but you did help unleash a monster on your home country and your loved ones. The solemn duty is upon you right now.

🧛 In addition to their marriage, Mina and Jonathan celebrate another sacrament, a sacrament of secrecy and oblivion. That Mina thinks of it as a sacrament is clear from her wording “an outward and visible sign,” echoing St Augustine’s definition of a sacrament as such a sign “of an inward and invisible grace.”

But keeping secrets from each other is rarely a good idea in a horror story.

25 August: Bedroom scene

Poor Lucy, all alone in her bedroom with the scratching and flapping at the window. Even though Arthur is visiting. I choose to read this as an indictment of Victorian sexual morality and how its strictures against even engaged couples cohabiting left young ladies unprotected against magical creatures of the night. Fortunately today we are more enlightened. 🙂

Figure 21: Lucy in bed, from Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

As @ivlia commented on this movie still, “that woman is neither sadly pale nor wan-looking, she’s just British 🙄.” If Lucy has the famous English peaches-and-cream complexion, though, by now it’s very easy on the peaches, and heavy on the cream.

30 August: Another dating discrepancy

Lucy’s reply to Mina raises two problems for the literal-minded nitpicker. First, “an appetite like a cormorant” suggests she eats a substantial fraction of her own weight in fish each day.

Second, it’s been 4–5 days since we last saw Lucy, and she was having a relapse of all her symptoms from Whitby. And – spoiler – Arthur is so worried for her that he’s about to call a doctor. Yet she tells Mina she’s sleeping well and full of life.

A plausible and charming explanation is that Lucy bravely covers up her health scare so as not to ruin her friend’s newlywed happiness.

Or perhaps the letter has been misdated and was in fact sent before 24 August, anticipating Mina’s letter of the same date.

That would be another dating glitch right after the week Seward seemingly passed in a day.

The dating, we’ve seen, is important because it establishes a chronology that fingers Dracula’s movements as the cause of both Renfield’s and Lucy’s symptoms.

But what if that isn’t true? What if someone has edited the dates to give that impression, and made a botched job of it? And why? Why would it be so important that we believe this foreigner is a vampire who has contaminated Lucy? Might someone have committed crimes they feel a need to justify? Hmm.

1 September: An awkward doctor’s visit

If this were a romantic novel, Lucy might be having second thoughts about Arthur, be secretly pining for Seward, or at least be ready to have her eyes opened when the doctor dashes in to save her life.

How convenient, then, yet how awkward given everybody’s sense of honor etc., for Arthur to be called away just as he has invited her other admirer to come, take her pulse and look deeply into her eyes.

Spoiler: This is a horror novel, and there will be sadly little bodice-ripping to show for this build-up, so I might as well spoil the anticlimax now. We’re a good month away from anyone even pulling open their shirt (but what a pulling open of the shirt it will be).

Ahem. Anyway. Back to analysis. Uh … I’m still wondering what the dying-parents theme is for, except conveniently keeping characters away and in the dark about what’s going on.

2 September: Enter Van Helsing

“I did not have full opportunity of examination such as I should

wish.” 😉

I bet, Seward.

Also:

- What Dr Seward thought he wrote to Arthur: “Don’t worry, Lucy’s not physically ill, but just to be sure I’ve asked a colleague to take a peek, a really great guy btw.”

- What Arthur will read: “Dear Art, Lucy is so fatally ill I’ve got a top European authority to rush all the way from Amsterdam. He’ll clearly strike you as bonkers, but trust my slightly unhealthy adulation for the man, I’m a doctor.”

Van Helsing has now entered the chat. Get used to his charming continental speech patterns and sentimentalism.

Figure 22: Trust me, I’m a doctor. Anthony Hopkins as Van Helsing in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Also, we learn that van Helsing owes Dr Seward because Dr Seward has sucked him. Uh, sucked gangrene from his wound, yuck. An oddly specific bond in a vampire story. Does this make Dr Seward vampire-ish? Is his devotion to Van Helsing akin to the mystic’s to the wounds of Christ (cf. Catherine of Siena)? And are we supposed to see some kind of homoerotic subtext here, cf. “The love that dares to speak its name”? Too many theories, not enough data.

3 September: Pouf!

Dr Seward gets told ‘Pouf!’ and is sent to smoke a cigarette in the garden while Van Helsing examines the lovely Lucy thoroughly. Alone in the garden, Dr Seward goes into a shy little dance routine and sings “Mr Cellophane,” ending the number by apologizing for taking up too much of the audience’s time. Okay, I made up that last bit, but it fits.

4 September: Zoophagy

Lucy’s doing better and, from the last change in Renfield’s behavior, we may infer it is because Dracula is back in residence at Carfax.

Renfield, after being abandoned for ten days, had just resigned himself to having to “do it for himself.” Do what? Apparently, appropriating the life force of other beings by consuming them alive. He has been looking to the master of this art, Dracula, to show him the way.

But failing that, Renfield’s DIY method is feeding other creatures to each other, bioaccumulating their life force up a makeshift food chain with himself at the top.

We may wonder why Renfield had an attack of frenzy at noon on 3 September. It must be to do with his link with Dracula. Is it sympathetic? Did Dracula throw a tantrum over van Helsing’s meddling with Lucy? Perhaps it is a withdrawal symptom because Dracula’s influence, as one might expect, is at its lowest ebb when the sun is high?

That seems unlikely, since Seward said it was at an unusual time, which argues against it being anything to do with Dracula’s regular biorhythm (necrorhythm?). But actually, we will learn by the end of the month that noon and sunset are significant times in Dracula’s biorhythm, for a specific reason of Stoker’s vampire lore that makes very little sense to me in terms what we now think of as the canonical lore.

6 September: Amsterdam–London

“Do not lose an hour.” So how many hours does Van Helsing need to get from Amsterdam to London, in this great age of late-1800s globalization, if he does not lose a single one? (original thread)

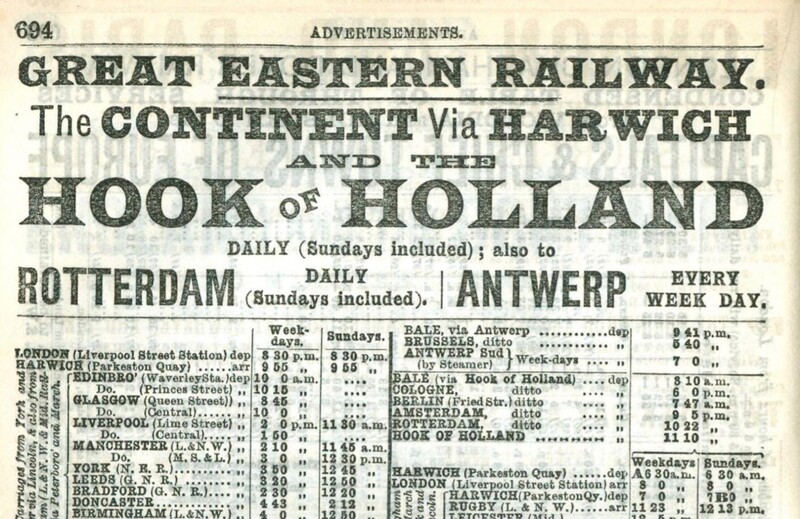

Let’s do like Dracula and study Bradshaw’s General Railway and Steam Navigation Guide (June 1896, no. 755, p. 694), where the Great Eastern Railway assures us the quickest route via Harwich and the Hook of Holland takes 11 hours.

Archive.org is an absolute treasure

Assuming the same schedule, if Van Helsing gets Seward’s telegram in the evening, he must catch the 9:05 pm to the Hook of Holland, where he’ll board a steamship that sails two hours later and brings him to Parkeston Quay in Harwich in seven hours or so. From there it is an hour and a half by rail to his 8 am arrival at Liverpool Street Station in London. Which, indeed, is where Dr Seward will meet him tomorrow.

(Today the EuroStar London–Amsterdam is 3h52m.)

7 September: Blood transfusion

It has now come down to a race between an ancient superstition and modern 19th-century medical science as to which one will kill Lucy first.

At this point human-to-human blood transfusions have been carried out in England for many decades (since Blundell’s success in 1818), but it’s still hit and miss. Karl Landsteiner’s crucial discovery of blood groups is yet to come (ca. 1901) and will take longer yet to inform medical practice.

Arthur’s “strong young manhood” is clearly important for ideas the story wishes to convey here. For Lucy’s sake, however, the manliness, brightness, and nobility of Arthur’s blood matters less than whether it is matched with her blood type or will trigger a dangerous immune reaction. But no-one knows this yet.

Unlike vampire bats, Victorians also have not yet figured out how to make an anticoagulant that won’t kill the patient. Blood clotting is a constant problem. To solve it, they sometimes resort to defibrination: take a pint of blood, add glass beads and stir vigorously to induce clots of fibrin to form, then extract them. (I imagine it like the skin on cocoa, but I probably imagine it wrong.) The remaining blood will be less prone to coagulation. However, the procedure involves increased risk of contaminating the blood.

I’m not a doctor, but I suspect the reason Van Helsing gives for dispensing with defibrination is nonsense. Despite all this, though, I’m also guessing that Van Helsing is making the right call, because the imminent risk of Lucy dying for want of blood outweighs all the other risks Van Helsing can do little about with the knowledge of his time.

And hey, at least it’s human blood, not goat, so it’s best practice, for 1890s values of best practice.

In other news:

- I am glad that Dr Seward understands Van Helsing’s parable of the corn, because that makes one of us.

- Van Helsing clearly already has a pretty good idea what made those wounds that Lucy has sexily covered up with a black velvet band. But he’s not about to let on to Dr Seward against what menace exactly he is to stand guard the whole night. Because that would be helpful.

8 September: A poll

Two kinds of people. Which one are you? The doctor or the damsel, the insomniac or the somnambulist?

Sleep is:

[ ]The boon we all crave for[ ]A presage of horror

I asked the Mastodon community; respondents (N = 4) skewed heavily insomniac. (See the poll)

9 September: Yet more odd dating

Lucy is feeling oddly close to Arthur, ironically unaware of how much of him she’s got pulsing right inside her veins. Dr Seward has been going for at least 36 hours without sleep.

They’re booth a bit woozy, and so is the dating of their diaries: by my count, Lucy and Seward are both writing about last night; Lucy’s should have been dated 8 Sep, but Seward falls asleep, so it makes sense that he writes today – except his waking up will be dated tomorrow. 🤔

—

In other news, Renfield would have been huge on TikTok.

10 September: What big teeth you have

(Or by my reckoning, still 9 Sep). Lucy’s lost blood again while Seward slept. In the absence of thoroughbred studmuffin Arthur, Van Helsing has to settle for transfusing Seward’s lower-quality commoner nerd blood. (Or maybe all that was just an excuse because he’s fond of his student; he doesn’t want to drain him today either.)

“No man knows, till he experiences it, what it is to feel his own life-blood drawn away into the veins of the woman he loves.” Seward’s pride must be a mixed feeling; this is probably not quite how he imagined spending the night with his beloved and pumping his bodily fluids into her. And yes, I think we’re supposed to see a sexual metaphor in the transfusion. Van Helsing certainly expects Arthur to see it, which conveniently explains why Arthur must be kept in the dark again.

Meanwhile, Lucy’s teeth seem to have grown.

Shrinking gums create this impression in corpses. The skin around fingernails also retracts as it desiccates. The resulting false growth of teeth and nails in the grave has been suggested as one explanation for the folk belief in vampires.

Ironically, being a medical man, Seward is so aware of the natural explanation that he ignores the possibility of vampirism: that the reason why her teeth are so big is THE BETTER TO EAT HIM.

11 September: Garlic

“Aha, my pretty miss, that bring the so nice nose all straight again. (…) No trifling with me! I never jest! There is grim purpose in all I do; and I warn you that you do not thwart me.“ It’s sometimes hard not to want Dracula to rip Van Helsing’s throat out.

Also, 1890s online shopping: wow. Van Helsing telegraphed only yesterday, and a cartload of garlic all the way from Harlem was delivered at the Westenras’ door today. Suck on that, Bezos.

Also, vampire lore: garlic has just entered the story as a general apotropaic. Van Helsing thus goes beyond Stoker’s notes on garlic, which only reference the more topical application in Emily Gerard’s Transylvanian Superstitions (cutting the vampire’s head off and putting it back in the grave with the mouth filled with garlic). Gerard does also mention the “Saxon” superstition that “Rubbing the body with garlic is a preservative against witchcraft and the pest.”

(Btw, the possibly related idea that placing raw cut onions in a room prevents disease is so widespread that the US National Onions Association, which is a thing that exists, has had to debunk it.

True story: someone I know actually found coworkers leaving onions around in the workplace to ward off the flu, which would have been less unsettling if the workplace hadn’t been a … medical laboratory 🙄)

12 September: Virgin crants and maiden strewments

“Virgin crants [and] maiden strewments”: For all her peaceful feelings and renewed cheer, Lucy is being morbid: She compares herself among the garlic flowers to the dead Ophelia being buried with garlands and strewn flowers in Hamlet, act 5, scene 1 (where it raises eyebrows because as a suspected suicide, Ophelia should not be so honored). Foreshadowing much?

13 September: My long habit of life amongst the insane

🧛 I have been urging our manly medical men to lose the DIY attitude and at least let the maids help keep watch. But today I guess we have all learned our lesson about how the most rational male devices can be undone by female foolishness, so I guess that’s off the table. What? No, we certainly haven’t learned that men should talk to women and tell them crucially important information. What a droll conceit!

🧛 Forgive me for harping on about dates, but did Lucy just have such a quiet night on 11/12 Sep that no-one bothered to record the progress in their diary, or has yet another day been mysteriously intercalated since Van Helsing left her wreathed in garlic? Both diarists are a bit woozy now, but still.

And on that note:

🧛 “I am beginning to wonder if my long habit of life amongst the insane is beginning to tell upon my own brain.” Aren’t we all, Dr Seward, aren’t we all.

17 September: The blood is the life

After a quiet spell, things are going down big time (thread).

🧛 “The blood is the life!” Renfield, having a normal one, is paraphrasing Genesis 9:4: “But flesh with the life thereof, which is the blood thereof, shall ye not eat.” Jews read this to say that kosher slaughter (shechita) must be carried out so as to quickly drain the animal of blood. Renfield, a lateral thinker, prefers to read it as “never mind the flesh, lap up the blood.”

🧛 The exhausted Van Helsing is off to Amsterdam and telegraphs to Carfax for Dr Seward to take over Lucy-watching, but forgets to say which Carfax. For want of a nail, the kingdom was lost.

🧛 “A great, gaunt grey wolf.” Enter Bersicker the wolf. And what a jump-scare entrance!

🧛 Exit Mrs Westenra, pursued by a wolf. Her doctor wasn’t kidding. A sudden shock did kill her.

🧛 No, the wolf in Lucy’s window is not Dracula, it’s a genuine wolf from Norway, of all places, but you’ll have to wait for tomorrow’s installment to learn what the heck it’s doing in Hampstead.

🧛 With the garlic arrangements disturbed and the room aired out a bit, Dracula is apparently free to come swirling in as a dust cloud. It seems odd that a supernatural horror like him needs to stoop to drugging the wine to deal with the maids, though.

At this point, @camilla_hoel wanted to know who did drug the maids, and suggested they might have done it themselves, spiking the doctor’s recommended glass of wine to steady their nerves further. – Well, when you have eliminated the impossible (like vampires), who had the opportunity? The maids, yes, certainly. Mrs Westenra herself, perhaps, over-indulging a habit. And wasn’t there someone else in the house that day? Someone with pharmacological knowledge? 🙂 And another suspicious character is about to turn up on the couch. Lots of suspects. – On the other hand, it seems from Jonathan’s account that Dracula enjoys devising human-level murder plots à la Agatha Christie, even to the point of impersonating Jonathan himself. So it may well be Dracula after all.

🧛 At long last we hear from Mina again. Life is good to her and Jonathan, and she’s busy home-making. She seems to have forgotten that Lucy had already told her the wedding date, but Lucy’s [BROKEN LINK: 08-30] letter may never have reached her, and as you may recall, something was off about that letter anyway.

But at this rate, is there even going to be any bride to marry on 28 September? The letter to Lucy is “unopened by her,” which can’t be good.

18 September: Exeunt Mrs Westenra and Peter Hawkins